Domenico Starnone’s novel The House on Via Gemito is a work of “autofiction” based on the author’s childhood and adolescence in a working-class family in Naples in the 1950s and ’60s. The narrator (Mimí) explores his fraught relationship with his father Federí– a railway clerk who has dreams of becoming an artist. Federí is extremely charismatic but at the same time bitter and resentful. He blames his lack of artistic success on the fact that, in order to support his family, he has to work an unfulfilling job in the railways. He also believes that other artists and critics are jealous of him and conspiring to ruin his career.

Domenico Starnone’s novel The House on Via Gemito is a work of “autofiction” based on the author’s childhood and adolescence in a working-class family in Naples in the 1950s and ’60s. The narrator (Mimí) explores his fraught relationship with his father Federí– a railway clerk who has dreams of becoming an artist. Federí is extremely charismatic but at the same time bitter and resentful. He blames his lack of artistic success on the fact that, in order to support his family, he has to work an unfulfilling job in the railways. He also believes that other artists and critics are jealous of him and conspiring to ruin his career.

One of the novel’s main themes is the fraught–and often abusive– nature of the relationship between Federí and his wife Rusinè. Federí is extremely possessive of his wife and often accuses her of being unfaithful to him. This ties in to his general suspicion of women’s sexuality. At the same time, he is extremely proud of his own success with women. As the novel begins, Mimí is trying to remember all the times that Federí abused Rusinè. His father insists that in all their years of marriage, he only hit his wife once. Mimí doesn’t believe him and this leads into a long section where he remembers fights between his parents, which in part revolve around his father criticizing his mother’s alleged vanity. Mimí also blames his father for neglecting his mother’s complaints about her health, which lead to her death at a relatively young age from a liver condition that would have been treatable if addressed at the right time.

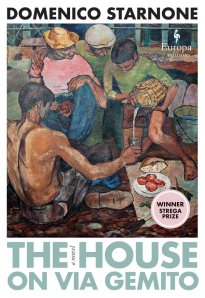

Another major theme of the novel is the process of making art. The second section of the book “The Boy Pouring Water” revolves around the period when Mimí posed for his father while he was in the process of painting his famous large scale work The Drinkers (a reproduction of which is used for the book cover). Starnone describes the tedious process of posing and the difficulty of having to hold the same position for a length of time. Mimí is determined to impress his father, who often complains that his other models are unable to stay still. He describes the process by which the artist makes order out of chaos–which is akin to how he turns his random memories into a coherent book. This section also includes the grown up narrator walking around Naples and trying to find his father’s paintings, which are hanging ignored in various municipal offices. Continue reading “Review: The House on Via Gemito by Domenico Starnone”

As a fan of Elena Ferrante’s

As a fan of Elena Ferrante’s  Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels — My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and The Story of the Lost Child — tell the story of two friends, Elena Greco (Lenu) and Raffaella Cerullo (Lina), from their childhood until their sixties. Though divided into four books, Ferrante has said that she considers the quartet to be one novel since it tells one continuous story.

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels — My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and The Story of the Lost Child — tell the story of two friends, Elena Greco (Lenu) and Raffaella Cerullo (Lina), from their childhood until their sixties. Though divided into four books, Ferrante has said that she considers the quartet to be one novel since it tells one continuous story.