In March 2017, a public prosecutor in Lahore, Pakistan, offered to acquit 42 Christian prisoners accused of murder if they converted to Islam. This prodded a re-reading of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, which also features a forced conversion—that of the Jewish moneylender, Shylock, to Christianity.

Written between 1596 and 1599, The Merchant of Venice centers around Antonio (the titular character) and his financial dealings with Shylock. Antonio’s friend Bassanio needs money in order to woo Portia, a wealthy noblewoman. In order to raise this amount, Antonio asks Shylock for a loan of 3000 ducats. The moneylender agrees on the condition that if Antonio defaults on the loan, Shylock will be entitled to a pound of his flesh. Antonio accepts these terms, since he has several ships coming in to port soon. However, Antonio’s ships are wrecked and he is forced to default. Shylock then demands his bond. At this point, Portia disguises herself as a man and acts as Antonio’s lawyer. She cleverly uses the terms of the contract against Shylock, since the moneylender is entitled to a pound of flesh but not to a single drop of blood—making fulfilling the bond impossible. Shylock is then charged with attempting to murder a Venetian citizen–as a Jew, he does not count as a Venetian– and his estate is confiscated, with one half going to Antonio and one half to the state. Antonio then offers to renounce his half of the estate, on the condition that Shylock become a Christian. The moneylender has no choice but to accept.

Though the play is classified as a comedy, it is problematic for modern audiences. Post the Holocaust, it is difficult not to feel deeply uncomfortable with the anti-Semitic portrayal of Shylock as greedy and fixated on money. The fact that he is forced to abandon his religion also seems deeply unfair given contemporary global norms. This discomfort with the play has led some to call for its removal from school curricula and for it to be taken off the stage. However, a close examination of the play shows that Shylock is by no means a two-dimensional villain, unlike Barabas in Christopher Marlowe’s Jew of Malta (often thought to have inspired Shakespeare’s play).

Early in the play, when Antonio first asks Shylock for a loan, the moneylender recalls how the merchant has treated him:

You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog,

And spit upon my Jewish gaberdine,

And all for use of that which is mine own.

Well then, it now appears you need my help:

Go to, then; you come to me, and you say

‘Shylock, we would have moneys:’ you say so;

You, that did void your rheum upon my beard

And foot me as you spurn a stranger cur

Over your threshold: moneys is your suit

What should I say to you? Should I not say

‘Hath a dog money? is it possible

A cur can lend three thousand ducats?’ Or

Shall I bend low and in a bondman’s key,

With bated breath and whispering humbleness, Say this;

‘Fair sir, you spit on me on Wednesday last;

You spurn’d me such a day; another time

You call’d me dog; and for these courtesies

I’ll lend you thus much moneys’? (Act 1, Scene 3)

Antonio routinely abuses Shylock, simply because of his religion. Yet now that he needs him, he has come to politely ask him for a loan. Shylock points out the merchant’s hypocrisy and asks why he should oblige him. Later, when he is asked what good Antonio’s flesh will do him, Shylock responds that it will serve as his revenge. In one of the play’s most famous speeches, he states:

Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will

resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian,

what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian

wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by

Christian example? Why, revenge. The villany you

teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I

will better the instruction. (Act 3, Scene 1)

In this speech, Shylock argues that Jews are just as human as Christians and experience all the same sensations and emotions. Just as Christians seek revenge when they are wronged, he will do so as well. By having Shylock make this speech, Shakespeare humanizes him and gives him a motivation for his hatred of Antonio and his relentless pursuit of his bond. Shylock is not pure evil. Rather, he is driven to seek vengeance for the ill-treatment he has received from the majority group.

Enter Ghost–Isabella Hammad’s second novel–centers around a production of Hamlet in the Occupied West Bank. The main character, a British-Palestinian actress named Sonia Nasir, has just ended a troubled relationship with a director in London and decided to visit her sister in Haifa (in today’s Israel) for the summer. While there, she reluctantly gets involved with the production of Hamlet, which is being directed by her sister’s friend Mariam. Meanwhile, Mariam’s brother Salim, who is a politician in Israel, has gotten caught in a controversy revolving around “colluding with the enemy” (i.e. Palestinians). During the course of the summer, the situation in Palestine becomes increasingly tense, with the Israelis blocking Muslims from praying at the Al Aqsa Mosque.

Enter Ghost–Isabella Hammad’s second novel–centers around a production of Hamlet in the Occupied West Bank. The main character, a British-Palestinian actress named Sonia Nasir, has just ended a troubled relationship with a director in London and decided to visit her sister in Haifa (in today’s Israel) for the summer. While there, she reluctantly gets involved with the production of Hamlet, which is being directed by her sister’s friend Mariam. Meanwhile, Mariam’s brother Salim, who is a politician in Israel, has gotten caught in a controversy revolving around “colluding with the enemy” (i.e. Palestinians). During the course of the summer, the situation in Palestine becomes increasingly tense, with the Israelis blocking Muslims from praying at the Al Aqsa Mosque. As a former Dramatic Literature major, I was very much looking forward to Mona Awad’s recently published novel All’s Well (August 2021), which revolves around Miranda Fitch, a Theater Studies professor at a New England university staging a production of All’s Well That Ends Well, one of Shakespeare’s lesser known plays. Miranda is a former professional actor whose career was ended by a fall from the stage while playing Lady Macbeth. After some hip surgeries, she is still dealing with chronic pain and with doctors who don’t take her seriously. Her colleagues also think that she is exaggerating her symptoms. One of her closest friends even tells her that perhaps her illness is in her mind. As the novel begins, she is also dealing with mutinous students who are upset that she has chosen to produce All’s Well, rather than Macbeth as they had wanted. The mutiny is led by Miranda’s nemesis, a student named Briana who always gets the leading roles because her parents are major donors to the Theater program.

As a former Dramatic Literature major, I was very much looking forward to Mona Awad’s recently published novel All’s Well (August 2021), which revolves around Miranda Fitch, a Theater Studies professor at a New England university staging a production of All’s Well That Ends Well, one of Shakespeare’s lesser known plays. Miranda is a former professional actor whose career was ended by a fall from the stage while playing Lady Macbeth. After some hip surgeries, she is still dealing with chronic pain and with doctors who don’t take her seriously. Her colleagues also think that she is exaggerating her symptoms. One of her closest friends even tells her that perhaps her illness is in her mind. As the novel begins, she is also dealing with mutinous students who are upset that she has chosen to produce All’s Well, rather than Macbeth as they had wanted. The mutiny is led by Miranda’s nemesis, a student named Briana who always gets the leading roles because her parents are major donors to the Theater program.

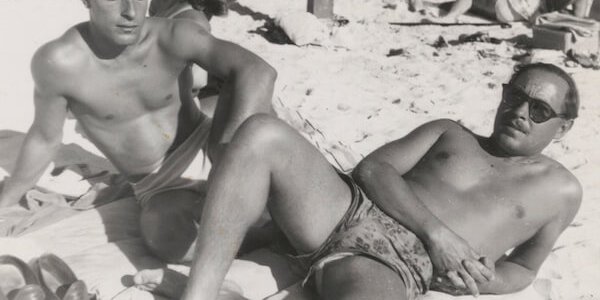

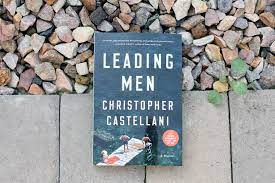

Since my undergraduate degree is in Dramatic Literature, I am very familiar with the 20th century American playwright Tennessee Williams, known for such classic plays as The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. However, even I had not heard of Frank Merlo, Williams’ long-term partner who died of lung cancer at the age of forty in 1963. It was during his partnership with Frank that Williams produced most of his best-known and successful works.

Since my undergraduate degree is in Dramatic Literature, I am very familiar with the 20th century American playwright Tennessee Williams, known for such classic plays as The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. However, even I had not heard of Frank Merlo, Williams’ long-term partner who died of lung cancer at the age of forty in 1963. It was during his partnership with Frank that Williams produced most of his best-known and successful works.